Drowning in Ideology

Public discourse about the “Islamic militant” has so overlaid the topic in doctrinal exotica that we lose sight of the individual

Among the hundreds of media articles, think tank papers and book publications on the topic of the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria, or ISIS, certain themes were prominent – did ISIS encapsulate the “real Islam”, why didn’t ordinary Muslims take a strong position against them, is radicalism the future of Islam? Such were the obsessions of the commentariat that social, economic, and political analysis of the phenomenon was hardly anywhere in sight. As if it was impertinent to ask whether there were drivers behind it other than the unbearable heaviness of Muslim being.

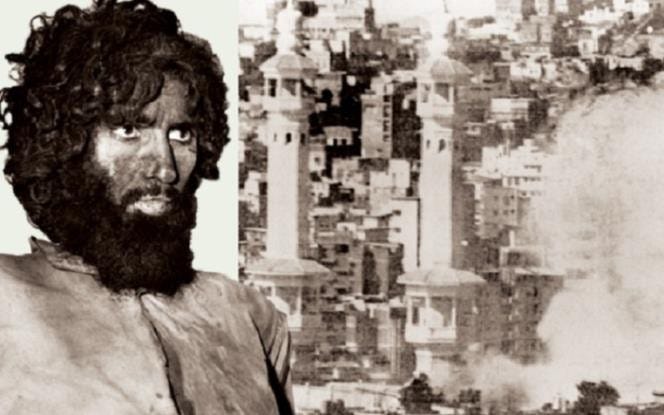

Here, I’m going to discuss a number of texts that fall under the rubric of modern “jihadism”: Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood ideologue Sayyid Qutb’s Maʿalim Fi-l-Tariq (Milestones), published just before his execution in 1966; Jihad, al-Farida al-Ghaʾiba (Jihad, the Neglected Obligation) by ʿAbd al-Salam Farag, a member of the Islamic Jihad group that assassinated Anwar Sadat in 1981; pamphlets written by Juhayman al-ʿUtaybi, who led the group that seized the Grand Mosque in Mecca in 1979; Jordanian religious scholar Abu Muhammad al-Maqdisi’s Millat Ibrahim (The Religion of Abraham, 1984) and al-Kawashif al-Jaliyya fi Kufr al-Dawla al-Saʿudiyya (The Obvious Proofs of the Infidelity of the Saudi State, 1989); al-Qaʿida leader Ayman al-Zawahiri’s Fursan fi Rayat al-Nabi (Knights Under the Prophet’s Banner, 2001); and speeches by ISIS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi.

To Rebel or Not to Rebel?

The fundamental unifying question addressed in these texts is, what are the conditions that justify insurrection against a ruler? In Milestones, his last book, Qutb elaborated his theory of the modern age as akin to pre-Islamic “ignorance” (jāhiliyya) in which the rule of God (ḥākimiyya) was absent. Qutb was writing in the context of a post-colonial regime that in its oppression of the Muslim Brotherhood to which he belonged seemed to have adopted the worst aspects of British rule, failing in its basic propaganda claim to have brought socio-economic justice to the people.

Qutb’s conceptual world and its language became a kind of template for the jihadist movement as it subsequently developed in the 1970s and 80s. Farag’s The Neglected Obligation introduced the concept of the near and the far enemy into what is an insurrectionist text. Rebelling against the ruler (the near enemy) becomes the primary obligation of the oppressed. “The rulers of this age were educated at the table of colonialism, whether that of the Crusaders, the Communists or the Zionists,” Farag wrote. In adopting Western political and legislative systems they have failed the Prophet by ignoring the duty to maintain the moral order of Islam. Now an “Islamic awakening” is needed to counter the “coups against the will of the people”.

Juhayman al-ʿUtaybi’s writings, produced in the same era, also focused o the question of the ruler’s right to rule and, in the Saudi Wahhabi context, the circumstances in which the individual citizen/Muslim may question that right. The group he led, al-Jamaʿa al-Salafiyya al-Muhtasiba (the Salafi Reckoning), rejected dealings with state institutions such as accepting jobs in the bureaucracy. These positions were also taken by the Egyptian Shukri Mustafa, a prison inmate during the persecution of the Muslim Brotherhood who was inspired by Qutb’s rejectionist views about the modern state. Shukri’s group often mixed with Juhayman’s during trips to Saudi Arabia. Nasir al-Huzaymi, a companion of Juhayman, relates in his account of the period how the two groups together sought the opinion of Nasir al-Din al-Albani, the Syrian cleric and founder of modern Salafism who was Juhayman’s mentor.

Muhammad al-Maqdisi, a Palestinian-Jordanian born in 1959, became familiar with Juhayman’s ideas through followers of Juhayman whom he met in Kuwait after the failed Meccan revolt. In his books he takes the ideas of the previous writers together to form an explicit case for action against Saudi rulers who ignore the traditional requirements of just Muslim rule, but, in the modern context, also follow a foreign policy that serves Western interests. He also attacks the religious scholars for cooperating with Saudi bodies of discourse control such as the World Muslim League.

Ayman al-Zawahiri’s Knights can more readily be read as Global South text against Western imperialism. Trained as an eye doctor, al-Zawahiri was no religious scholar, which had the effect of making his speech more directly political. He cites Qutb far more often than Ibn Taymiyya, the medieval theologian whose ideas are at the heart of the jihadist movements. “Sayyid Qutb’s call for tawḥīd and complete submission to the rule of God and sovereignty of the divine path was and remains the spark for the Islamic revolution against the internal and external enemies of Islam,” he writes.

Al-Zawahiri places the beginning of what he calls the Islamic movement (al-ḥaraka al-islamiyya) at Qutb’s death in 1966 but has an essentially Nasserist, Arab nationalist view of history. Britain prevented Egypt’s Ottoman governor Muhammad Ali from marching on Istanbul in the 1830s to replace weak Ottoman sultans because “he could have established a strong Arab state in Egypt or reinvigorated the Ottoman caliphate”. Muslims today need to establish liberated territory to use as a base for “ejecting the invaders from Islamic territories”.

Al-Baghdadi’s speeches were similarly political, if cloaked in Islamic language. Before his famous public sermon in a Mosul in July 2014, he issued a voice recording marking the beginning of the fasting month of Ramadan that called for righting historical wrongs. “The Muslims were defeated after the fall of their caliphate,” he began in one passage. “Then their state ceased to exist, so the disbelievers were able to weaken and humiliate the Muslims, dominate them everywhere, plunder their wealth and resources, and rob them of their rights. They accomplished this by attacking and occupying their lands, placing their treacherous agents in power to rule the Muslims brutally, using deceptive slogans such as civilization, peace, co-existence, freedom, democracy, secularism, Baathism, nationalism and patriotism.”

When the caliphate was declared several days later, ISIS propaganda claimed it had smashed the idolatrous “borders of humiliation” established by Britain and France after the First World War, and videos showed fighters passing through Iraq-Syria border checkpoints without passports as if ISIS had erased Sykes-Picot.

Rereading Jihadism

Socio-political readings of jihadism become less fashionable the closer they impinge upon contemporary realities. The context of mass repression in Nasser’s Egypt can be described without much controversy in any standard description of Sayyid Qutb’s writing: Qutb’s jihadism is granted its political context without contestation. But jihadism since that time has not fared quite so well, presented in Western media and academic narrative as a series of violent eruptions informed by ancient doctrinal absolutes and eternal historical hatreds.

Juhayman’s revolt is usually framed as a retrograde return to the fanatical Ikhwan revolt of the 1920s against King Abd al-Aziz’s attempt to build a modern state with British support. In his memoir, Nasir al-Huzaymi leans heavily into this interpretation, arguing that as a proud ʿUtaybi Juhayman wanted to avenge his Ikhwan ancestors. But as a Saudi national serializing his book in the Saudi press, al-Huzaymi was not in a position to cast Juhayman in a different light. Even still he is careful to state at numerous points that he disagreed with Juhayman over seizing the mosque. This perhaps gives him the space to state that Juhayman was interested in establishing “a just state” (dawlat ʿadl), and even that he had a “revolutionary sensibility” (ḥiss thawrī). What did he mean by that?

Juhayman composed 14 pamphlets that circulated in Saudi mosques in 1978 and 1979 the first of which is the most explict about his aims and inspirations. Titled Rafʿ al-Iltibas ʿan Millat Man Jaʿalahu Allah Imam li-l-Nas (Ending Confusion Concerning the Religion of Those Set by God as a Guide for People), what Juhayman does is present an argument that in its essence rejects forms of Westernization and any tyrannical system that ties to impose it. He states at the outset that he wants to clarify the nature of the religion of Ibrahim to demonstrate “the difference between truth and falsehood and show that, contrary to some claims, Islam is not a religion of ‘civilization’ that mixes East with West”.

He describes three types of Saudi ulama: those who focus on core Wahhabi bugbears such as combatting Sufism, visiting graves and other heretical innovations; those who devote themselves to scholarly pursuits such as hadith studies (a reference to Al-Albani); and those interested in controlling the levers of state and ideological threats such as communism, by which he means the Muslim Brotherhood. His objection to the first two groups is that they are silent about the state justice system’s application of Islamic criminal penalties to the weak but not the powerful, claiming there is little they can about it. As for the third group, they are too preocuppied with their own ideological project of “thought control” (taḥkīm al-afkār). None of them are willing to suffer for a higher principle.

Rather than an argument about religious ideology, Juhayman’s discourse is plainly about justice in a strikingly modern sense. Al-Imara wa-l-Bayʿa wa-l-Taʿa (The State, Allegiance and Obedience) starts with the statement that mosque preachers must “rule the people fairly, follow and not follow their whims” but in the Saudi state the devout classes have fallen into extremes: there are the uber-pious such as those working in the morality police (since disbanded) who take it on themselves to force others to live a puritanical life of worldly rejection and there are the state ulama working within government.

Islamic ideals have been upturned so that “the caliph is the one who imposes himself on [Muslims]”, not vice versa. As for the chief government cleric of the time, ʿAbd al-ʿAziz bin Baz, the Saudi rulers “take from him and his knowledge what suits them, but they would not hesitate to contradict him if he faced them with what is right, and he knows this well”, which is precisely the criticism that was later made of Bin Baz for his justification of hosting US troops in the 1990s. Juhayman then cites a prophetic hadith that offers Bin Baz the excuse that if his position does not allow him to speak out against a reprehensible situation (munkar) he should condemn it in his heart.

In their study of the Juhayman material, The Meccan Rebellion: The Story of Juhayman al-ʿUtaybi Revisited (2011), Thomas Hegghammer and Stephane Lacroix depict Juhayman’s movement as an aberration, intellectually and organizationally separate from other trends of the period, “characterized by a strong focus on ritual practices, a declared disdain for politics, and yet an active rejection of the state and its institution”. After elaborating on his apocalyptic thinking (a theme that also later preoccupied research into ISIS), they conclude that the texts “do not reveal a particularly clear political doctrine” and his movement was more driven by “ideology and charismatic leadership than by structural socioeconomic and political factors”.

Not only does this appear incorrect, but it is also not difficult to understand that Juhayman was responding to the considerable social, economic, and cultural dislocations of the 1970s, dislocations that Abdullah al-Ghaddami captured well in his book Hikayat al-Hadatha (The Story of Modernity). Al-Ghaddami points to the effects of sudden oil wealth, including shifts in Saudi urban topography as large cities were developed on an American model of wide streets and boulevards – “urban spaces devoid of any humanity”. We can add the dislocation of a political structure and foreign policy produced in the crucible of US neocolonialism, specifically the coup of 1964 that installed King Faisal as a bulwark against the spread of non-aligned Arab nationalism and the Soviet-backed Arab Left.

The Subaltern World

Once upon a time it wasn’t unusual or controversial to understand the jihadist in subaltern terms. In The Prophet and Pharaoh: Muslim Extremism in Egypt (1986), Gilles Kepel understood the Egyptian radical movements of the 1970s as a product of poverty and hopelessness in a post-colonial police state. Kepel was one of the first to understand Qutb as a reaction to totalitarianism and oppression. “The language and categories adopted by Qutb and his emulators captured the suffering, frustration, and daily demands of certain components of that society,” he wrote. In Qutb’s conceptual schema, everyone from the the prison guards to the president risked losing their status in God’s eyes as believers through their contributions, however big or small, to a failed society in its supposed state of post-colonial liberation. The only solution was for a vanguard to withdraw in preparation for the coming Islamic utopia.

Kepel notes how Egyptian state media presented the ideology and practices of Shukri Mustafa’s group in as ludicrous a light as possible during his trial in 1977, ensuring that Mustafa was seen as an “insane criminal” in rejecting state employment or participation in the education system or even learning to write. But if you were one of the millions of people who struggled against corruption and nepotism to obtain an education and then find government employment to be able to get married and set up home it might not appear so ridiculous. For Kepel, Shukri Mustafa’s group should be seen as part of an “impassioned revolt of the poor, the disinherited, and the hopeless” in Cairo’s slum belt, living symbols of “the failure of the independent state’s modernization projects”. Never again would Kepel be so sympathetic to his subjects.

Two decades earlier Frantz Fanon wrote The Wretched of the Earth (1961). Published just before his death, the book arises from Fanon’s experience of Algeria’s bitter struggle for independence from France, but it speaks to the failure of national elites across the Global South to realize the post-colonial national project, a failure that endures. In the decolonized state, there was/is “a masked discontent, like the smoking ashes of a burnt-down house after the fire has been put out, which still threaten to burst into flames again”; violence was/is a “cleansing force” that frees native from inferiority complex, despair and inaction; under the leadership of a corrupt national bourgeoisie, complicit with Western capital, countries became/remain the “brothel of Europe”. These searing descriptions could apply to any number of locations today.

Rejecting Exceptionalism

In the era of al-Qaʿida and ISIS, Islamic exceptionalism became the dominant trope in the jihadism industry. Social readings of foundational jihadi texts that go beyond the exotica of theology became decidedly unfashionable. The policy sphere seeped into the Western academe through the prism of “Security Studies”, reducing the space to think freely about militancy. Notions of cultural particularism – which came to dominate the Western academe after the 1960s – meant Islam could be held up as the explanation for a host of political, economic, and social phenomena. Insistent attention to the otherness of the militant functions too to delineate and define “the West” as everything the jihadist and his Islamic seeding ground is not. As Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak has written, this discourse serves the “desire to conserve the subject of the West, or the West as subject”.

Spivak once famously asked if the subaltern can speak. Her point was that subaltern actors normally do in fact tell us why they act as they do, but we are not necessarily capable, whether politically or discursively, of listening. There is no reason for us not to understand someone like Juhayman as a non-elite actor who challenged political tyranny and social injustice, but for some reason we have chosen for the most part not to. Convention has preferred the lens of “atavistically backward fanatical terrorists”, as Kepel put it, whose texts are mere manuals for inexplicable violence against the forward march of modernity. Yet we cannot say we lack the materials to know these figures from relatively recent history if we really want to.